Mistakes are unavoidable in life, yet this guide to common writing errors in stories (with explanations, examples and tips to avoid them) will help you develop your prose’s clarity, quality and impact.

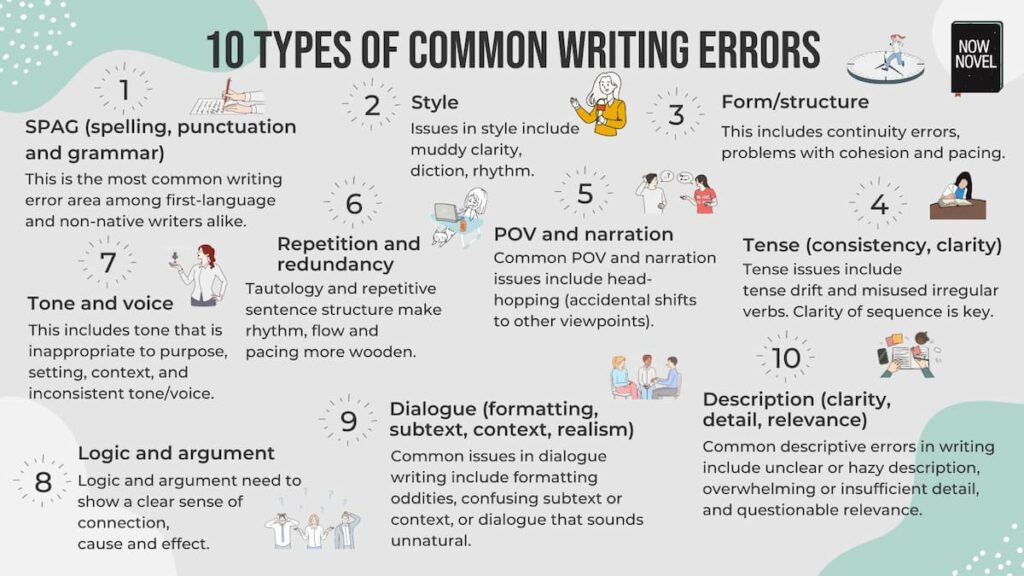

Common types of writing error

The following are ten areas issues often creep in. Keep reading for fifty-two examples of common errors in writing.

1. SPAG (spelling, punctuation, and grammar)

Spelling, punctuation and grammar mistakes are the most common writing error areas. They’re the easiest issues for eagle-eyed editors to fix (and also for reviewers or trolls to pick on). Always edit your work and invest in pro editing pre-publication.

2. Style (clarity, diction, structure, rhythm)

Issues of style include poor clarity (when meaning and inference are unclear). Incorrect diction, too, such as non-idiomatic word choice and words not having correct connotations and other diction issues. Keep reading for specific examples.

3. Form/structure (continuity, cohesion, pacing)

Common writing errors in form and structure include continuity errors (no disappearing Chekhov’s Guns unless there are reasons, please). In addition, problems with cohesion (how and where events connect) and pacing.

4. Tense (consistency, clarity)

Common tense issues in writing include tense drift (when you’re reading and suddenly you were reading a different tense – ‘were’? That should be ‘are’). Clear sequences and timelines are key.

5. POV and narration (depth, shifts, knowledge limitations)

POV and narration are closely related. Common writing issues involving both include head-hopping, depth issues that reduce impact, and disregarding fixed POV knowledge limitations, such as what a first-person narrator can know about another person’s thoughts without interpretation of expressions or gestures or verbal, written or telepathic communication.

6. Repetition and redundancy (tautology, pleonasm, repetitive sentence structure)

Repetition and redundancy turn the chugging along of story’s engines into the Little Engine that Couldn’t. Tautology, pleonasm and repetitive sentence structure make rhythm, flow, and pacing more wooden.

7. Tone and voice (appropriateness, clarity, consistency)

Common tone and voice issues in writing include tone that is inappropriate to purpose, setting or context, and tone and voice that change without explanation (poor consistency).

8. Logic and argument (circular reasoning, generalization, false cause and effect)

Logic and argument shouldn’t make readers scratch their heads in bewilderment. Action and reaction, cause and effect – the foundation of understanding is logic that enables connection, the resolution of incomplete equations.

9. Dialogue (formatting, subtext, context, realism)

Common issues in dialogue writing include formatting oddities, confusing subtext or context, or dialogue that sounds unreal (e.g. ‘As you know, Bob’ dialogue).

10. Description (clarity, detail, relevance, ratio)

Common errors in description writing include unclear or hazy description, overwhelming or insufficient detail, thin relevance, and pacing-diminishing imbalance between description and other elements (such as action, dialogue, in fiction writing).

Now that we’ve summed up ten broad categories of common writing mistakes, let’s jump in and look at individual examples:

SPAG errors: Examples and tips

SPAG (spelling, punctuation and grammar) is an ugly acronym for the easiest to make (and sometimes inadvertently funny and thus fun for an editor) error. The dessert is hot? Fine. But wait, what are those camels doing in it?

Common SPAG errors include:

Common spelling errors

Confusing possessive pronouns with contractions

E.g., Your (the possessive) and you’re, the contraction of ‘you are’ (such as when a reader commented, ‘your [sic] a dick’). Or its (possessive) and it’s (contraction of ‘it is’) – it doesn’t help that we use apostrophes to form nouns’ possessives as well as contractions (nobody said English was easy).

Mixing up homonyms

Homonyms are words that sound the same phonetically. ‘Their’ and ‘there’ are commonly confused (because we use both so often, plus the first three letters are the same so it’s easy to automatically write the wrong one).

Other commonly confused homonyms include ‘pouring’ (the present participle for emptying, say, a jug) and ‘poring’ (reading or studying a document or artwork with intent focus).

Mixing US/UK/AU/CA English spellings

It is best to use one regional English spelling type throughout a piece of writing (except for, for example, showing a letter written by a British character in a story narrated by an American and similar cases where using both makes sense for the story due to a special case).

There are three main differences between spellings in Commonwealth countries that use UK spellings and US spellings:

a) Per the standardizations Noah Webster made, the US uses ‘o’ instead of ‘ou’ (in words such as harbor (US) and harbour (UK).

b) ‘S’ instead of ‘Z’ in words such as realize (US) and realise (UK).

c) Single ‘L’ consonants in words such as traveler, jeweler (US) vs double in the UK (traveller, jeweller).

Spelling Mnemonics and Exceptions

Other examples that trip many writers up are English’s many exceptions.

Many will remember, for example, the spelling mnemonic (memorization) phrase ‘I before E, except after C’. [Ed’s note: I learned this as a kid from a fun episode of the animated Peanuts series involving a spelling bee.]

We have ‘believe’, ‘reprieve’, ‘conceive’, ‘deceive’ which fit the rule. Yet what about species, science, ancient? One simply must learn the exceptions (and look up the exceptions when in doubt). Some follow their own pattern (e.g., where ‘C’ is pronounced as a ‘sh’ sound, it is typically ‘I’ before ‘E’ still, such as ancient, efficient).

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO SCENE STRUCTURE

Read a guide to writing scenes with purpose that move your story forward.

Learn moreCommon punctuation errors

Some punctuation is for effect, and like the pepper and salt of language, should be used sparingly. Nobody wants an exclamation mark overdose to push up their editor’s blood pressure.

Tweet This

Common types of punctuation error include:

Comma misuse

A ‘comma splice’ is where a comma separates what should be two sentences.

For example: ‘I was anxious for the recital, I forgot to breathe.’

Another is omitting commas in lists (‘I bought chocolate eggs toothpaste and regrettably bad frozen pizza’) – because no commas are used, the reader doesn’t know whether the eggs are chocolate ones or the less exciting chicken-y kind. Commas often change the meaning of a sentence (such as in the classic, ‘A panda bear eats, shoots, and leaves’ example).

Misplaced apostrophes

Has apostrophe placement in the phrase ‘two weeks’ notice’ ever given you trouble? You’re not alone.

Oxford International English Schools lists bungling apostrophes as one of the most common English usage errors.

Overusing exclamation or question marks

This technically falls more under ‘style’, yet it is a common beginner’s mistake.

Good style generally considers a single exclamation mark or question mark sufficient to express declamatory/excited or questioning tone.

An exception is the interrobang (written !? (US) or ?! (UK)), which combines a questioning and exclamatory effect (but is not used in formal writing).

Forgetting to open/close speech marks

This creates havoc for the reader trying to understand where speech and narration begin or end.

It’s an example of the small punctuation errors that make proofreading after copy-editing essential before publication.

Incorrect use of ellipses

Ellipses, used to express trailing off, a longer pause or inference of the unsaid, always consist of three periods only.

They may either be written with a space before and after each period (“Well . . .”) or like a three-letter word between words (“Well …”) or can be inserted as a special character with a space on either side (Alt + Ctrl + . on a Windows device in Word).

A benefit of using the special character is you won’t get ‘orphaned’ periods wrapping to the next line (the device becomes a single-word unit). One caveat: the character-insertion approach may not show consistently the same across multiple softwares or readers).

Other common punctuation errors include faulty use of dashes and hyphens (such as forgetting to hyphenate compound nouns and adjectives) and incorrect use of brackets. See more about hyphen and dash use via Grammarly here.

Common grammar mistakes

Grammar mistakes are often the trickiest errors to correct (but also the most fun in creating surprise comedic effects).

Common grammatical errors include:

Subject-verb agreement issues

The subject and its verb should match in number or tense. E.g., ‘The team was cringeworthy in the lackluster choreography they did to ‘My Humps’ before the match.’ (Not ‘were’, which would work with the plural subject, ‘teams’.)

Dangling modifiers

A dangling modifier is a phrase or clause not clearly related to the part of a sentence it modifies. It’s a common source of unintentional comedy.

E.g., ‘Running late to watch the movie, a bird pooped all down my friend’s forehead’ (Ed’s note: This did happen to a friend of mine once, though we still made it to the movie).

The clear subject (e.g., ‘My friend and I’, ‘we’) should be included in the sentence. One fix: ‘We were running late to watch the movie when a bird pooped all down my friend’s forehead.’

Misplaced modifiers

Awkward sentence structure that introduces ambiguity, such as clause sequences which create confusion about who the subject performing an action is:

‘I saw a family of geese driving down the street’.

(Unless geese are coming for Vin Diesel’s gig fast and furiously, it would be clearer as ‘Driving down the street, I saw a family of geese.’).

Run-on sentences

Two or more clauses not separated by the appropriate punctuation.

Example: ‘Today was the last straw it was the day my sister ate the chocolate I had been keeping for my piano teacher.’

There should be a period and new sentence after ‘straw’ (since the previous sentence is grammatically complete).

Confusing comparatives and superlatives

For example, ‘He is the most rudest prince in all the land’ (the phrase doesn’t need ‘most’ since ‘rudest’ would imply the pinnacle of rudeness, the greatest degree of comparison).

Another: The incorrect use of a superlative form for an incomparable quality: ‘The most unique was…’.

Because ‘unique’ is an absolute quality meaning ‘one-of-a-kind’ (and thus beyond compare) the comparatives ‘most unusual’ or ‘most precious’ (or another option) would be correct to use instead.

Spelling, punctuation and grammar aren’t stable across eras, ‘Englishes’. You may have a character who did not have the privilege of much formal education, or who did but forgot and doesn’t read, or a character for whom English is not a first language, and thus ‘doesn’t English good’, for example. You may have a character who says ‘the most unique’. Sometimes we know ‘better’ than our characters, sometimes not.

The best rules to break are still the ones you know you’re breaking for reasons relating to context, character, milieu or effect.

Tweet This

Tips to avoid common SPAG mistakes

To avoid common spelling, punctuation and grammar mistakes:

- Run your writing through a language checker. For example, Word’s built-in editor, Grammarly or ProWritingAid. Tools won’t catch everything (and will often false-flag non-issues such as writing where you’ve deliberately used a different region’s spelling), but you’ll catch sneaky typos that snuck in.

- Edit from print copy. Many writers swear by printing out proof copies to work from. The switch from digital to physical print has benefits – there’s no ‘infinite scroll’, for one, encouraging you to scan through too hastily. It’s like seeing the text with new eyes after a break.

- Consult style and grammar guides. A good style guide such as Strunk & White’s Elements of Style or The Oxford Essential Guide to Writing is useful to have in your collection, as well as go-to spelling and other reference resources such as dictionaries and thesauruses.

- Keep a checklist of SPAG errors you make habitually. It may be incorrect comma placement, using dangling modifiers, or another error. Going through to check for a list of errors and ticking them off may help you make error-nuking a more satisfying, systematic process.

- Read widely. The more you read, the better your innate sense of good SPAG will become.

- Get feedback. Many members in Now Novel’s crit community pinpoint spelling, punctuation and grammar issues (you choose whether to ask for feedback on this category in the flow of crit submission).

Watch a summary of this article

Share your thoughts in the comments!

Style issues: Examples and tips

Style may seem a more nebulous category than spelling, punctuation and grammar. After all, it concerns aspects ‘rhythm and flow’, the music words make, and ‘diction’ (word choice and voice).

Yet good style makes writing that much more satisfying and impactful.

Common style issues in writing:

Low Clarity (Vague, dense or ambiguous language)

Clarity ensures readers are able to make sense of a text. Is the language used easy to understand, unambiguous in meaning? Are images clear and precise?

Example: ‘The report was prepared by the committee, and it contained several recommendations for the board to consider.’

Rewriting this with greater concision and clarity:

‘The report that the committee had prepared made several recommendations to the board.’

This eliminates issues such as pleonasm (see below). It also suggests sequence clearer in the use of past perfect to describe the preparation preceding the recommendations being made. It leads us through two related processes in clear sequence.

Faulty capitalization

Common nouns such as ‘school’ or ‘mother’ should be lowercased, except when they are part of a formal title or salutatory address (e.g., Little Ships High School, or “Of course, Mother,” the vice president said to his wife …’).

Overusing adverbs or adjectives

A winding, verbose, tangled, excessive, fussy sentence can become annoying to read (if it’s every other sentence). It’s like Uncle Colm in Derry Girls – slow to get to the point. The same goes for excessive adverbs (the road to hell is paved with those, according to Stephen King).

Jargon or Niche language

If your characters need to DM the NRA to talk about the VIPs visiting the YMCA to discuss the NDAs relating to the NSSAs, your reader may tire with all the acronyms and in-group or niche-specific language. Writing should not need a user manual or exploded view.

This is a particular hazard in sci-fi and stories with strong technological aspects, where there may be a fair amount of exposition about how things work. Think about the user experience. Describe that.

Monotonous sentence structure

All long sentences, all staccato sentences – neither is ideal. Varying sentence and paragraph structure sometimes for rhythm and flow will keep your writing engaging, moving and rhythmically interesting.

Clichéd imagery and expressions

Clichés weaken style because they make voice read like a dead man’s echo more than a living, vital thing. Single tears rolling down, thunder and lightning on a suspenseful night – clichés that a reader may groan at (or relish pointing out in a review – another easy target).

Tips to avoid common style issues

How can you avoid some of the most common style issues in writing?

- Read writing aloud if unsure. The ear catches convoluted, awkward structure and phrases that make you say, ‘Huh?’

- Pick a style reference source and stick with it. For example, you might follow the Chicago Manual of Style’s guidelines on when to capitalize what. CMoS’s Q&A forums are a great source for niche style-related writing questions and answers, too.

- Be consistent. This follows on from the previous tip. If you spell your main character’s name five different ways, or they have five different nicknames that aren’t ever contextually explained, you could confuse your reader.

- Replace adverbs with verbs that do the heavy lifting. For example, instead of ‘She ran fast’, you might say ‘she hurtled’ or ‘she sprinted’. This is stronger for impact as well as connotation, each specific verb having its own more specific connotations (‘sprint’ comes from the Old Norse spretta meaning ‘to jump up’, with a sense of being startled into action).

- Keep the most impactful, expressive adjectives. For example, in, ‘He had kind, brown, slightly small eyes’ which is the most important descriptor? Many would say that which gives character – ‘kind’.

- Define or explain technical terms using similes, analogies. For example, you could say ‘Worm XG19V entered network 2B’ or you could say ‘The worm entered the bank’s (previously thought to be) most secure network with the silk-gloved stealth of an assassin.’ Specificity and generous contextualizing win.

- Draw figurative language from your story’s world. Instead of someone being ‘dead as a doornail’, what image of death would be foremost in a character’s mind in your world? Use that. Dead as the last king. Or as Cemetery Boulevard on a Sunday at midnight. Dead as Woofles who we buried under the Jacaranda when I was five.

Form and structure issues: Examples and tips

The terms ‘form’ and ‘structure’ are often used interchangeably.

Continuity errors are structural ones. If a scene ends with a grizzly death, there’d better be contextual or explicit clarification why the deceased is fine and dandy at the start of the next chapter. Or else the reader may get annoyed by continuity errors and pick a new read.

Common formal and structural issues in stories include:

Low cohesion

Some genres are bigger sticklers for cohesion than others.

If you’ve ever watched anime, for example, you may be surprised that a seemingly calm conversation can become a screaming match with high conflict in a matter of seconds.

Yet most narrative fiction needs cohesion. Why is cohesion in a story important? Because it helps to create a sense of unity and continuity throughout the narrative.

Cohesion refers to the way that different parts of a story are linked together, weave together a whole. Because in Chapter 1 a murder is uncovered, the gathering of evidence in Chapter 2 makes sense given what’s come before. There is cause and effect. No conflict without a cause (even if the cause is not revealed immediately, the author playing with time, concealment vs revelation).

Stories without a clear sense of cause and effect make it hard to guess the relative importance of events, what information matters more, vs less (and how each event connects to others).

Clunky proportion between elements or Acts

If it takes up to the penultimate chapter of a book for the inciting action to occur, for the story to feel like the reader is on their way, that’s an issue of proportion.

Exposition should ideally be proportional to development which should be proportional to resolution. Of course some stories start developing from the first line. Others are slow burns. Yet when the balance is off, the reader knows.

Rushed beginnings, middles, or endings

Just as exposition that takes too long to get to the punchline (or rather, the next development), like a poorly structured joke, is too slow, rushed segments are also formal issues.

A sense of rush in formal structure could be due to:

- Insufficient detail or description: Have you taken the time to give the reader setting detail, specific visual imagery?

- Authorial impatience: You may be impatient to get to the end of this draft, and to get your story out into the world, but don’t let the reader see this between the lines

- All core plot with no subplots, side avenues: It could also be that the story is rigidly following a predetermined plot and could explore subplots that relate to (and deepen the themes, characters, ideas of) the main storyline [Ed’s note: I caught a misplaced bracket here the day after publication. Remember: Nobody’s perfect, we learn from mistakes].

Unrealistic, inconsistent or non-existent character development

In some genres, characters may have flat arcs (like in the Bond franchise where our James doesn’t develop much).

Yet it may read as a structural oddity if a character suddenly finds bravery, empathy or another trait out of nowhere (the story arc does not help to explain the why of the character’s change).

Just as unrealistic character development gives change without a sense of any rhyme or reason behind it, inconsistent development where characters go back and forth on what are usually stable traits (such as core values, beliefs, ideals) with no explanation may confuse readers and make arcs seem erratic or like the author’s making it up as they go along without any destination or purpose in mind.

Lack of conflict or tension

Stories need conflict and tension. Just as life does. There’s a reason Franz Kafka represents bureaucracy as a kind of hell. Hell is boring, repetitious torture with no promise of an end like in the myth of Sisyphus, rolling that boulder up a hill.

Tweet This

Conflict and tension help to delineate a story’s structure. In the hero’s journey, as the final confrontation looms, the reader knows they’re nearing the end (ditto the romantic union in a feel-good romance).

Tips to avoid common form and structure errors in stories

To check that your story’s structure is satisfying and propels events forward:

- Review the length of chapters and other segments. Which is your longest, and which are your shortest segments? Does the longest need a well-placed scene-break somewhere? Or could it be split into two at a nail-biting moment to create hooks between chapters? Do the shorter chapters need any expansion, coloring in of detail, development?

- Check if cause and effect are clear. If you never outlined your story to start with, consider creating a reverse outline, a short paragraph or even sentence per chapter. This will give you a condensed view of what happens, when (and help to underline where any causes or effects may seem thin or missing). It’ll also come in handy for creating a synopsis for querying purposes.

- See where the story needs coloring in and cutting back. Sometimes we overwrite and sometimes we write too little. What isn’t colored in enough, and is there any passage with too much of a welter of detail which is slowing pace?

- Create timelines. You may wish to create a timeline of events that involve your main characters. Write a one-line summary of how each changes your character as you go. What are the dynamic moments (highs, lows, turning points) of their progress?

- Try some planning. It might just be writing down where your opening scenario ends. Or else making a detailed chapter by chapter story outline. However much prewriting you do, this will help you solidify more of the scope and shape of your story upfront (even if you depart from the outline you’ve written completely by your final draft).

How do you ensure structure and form in your story stay cohesive? Share your process in the comments.

GET FEEDBACK IN A CARING CRIT COMMUNITY

Get honest, thoughtful feedback from writers of all ages and stages in their craft and process.

LEARN MORETense errors: Examples and tips

If tense makes you tense, put that in the past with these tips and explanations of why tense issues in writing occur.

Types of tense issue include:

Inconsistent tense use (Tense drift)

Tense drift refers to when verbs’ tenses change unexpectedly for events context tells us are in the same timeline.

When tense drifts, the sequence of events becomes confusing. For example:

Because I had forgotten my homework I will lie to the teacher and hope I wasn’t given detention.

The whiplash between past perfect tense (had forgotten), future (I will lie) and the negative form of simple past tense (wasn’t put) is disorienting.

Events in the same timeline should use the same tense, unless other details are added from other times, such as prior events, or hypothetical or conditional situations.

Clearer:

Because I had forgotten my homework, I lied to the teacher in the hope I wouldn’t be given detention.

The tense in this corrected example flows thus:

- Past perfect tense used for events/conditions preceding a simple past timeline (‘Because I had forgotten…’)

- Simple past tense used for past events later than the already-happened events or prior conditions (‘I lied to the teacher…’)

- Conditional tense used for possible future events following on from the past scenario (‘I wouldn’t be given detention.’). More on conditional tenses below.

Mixing perfect tenses

Past, present, and future ‘perfect’ tense are often confusing, leading to ‘imperfect’ usage.

- Past perfect: I/you/we/they/she/he had been changing [prior to other events]

- Present perfect: I/you/we/they/she/he have/has been changing [which brings us to the present moment]

- Future perfect: I/you/we/they/she/he will have been changing [when some future event will occur]

These are all examples in the active voice and indicative mood. [Ed’s note: I strongly recommend Ursula K. Le Guin’s writing manual Steering the Craft for tense explanations, in ‘Appendix II: Forms of the Verb’. It is the best explanation of uncommon tenses I have ever come across, plus her wit is always fun.]

If you were to write ‘I have been changing when I decided to rob that bank’, the reader is likely to be confused about the sequence of events, expecting (from the present perfect at the start) a clause referring to current events (‘I have been changing, or trying to, but I’m going to rob that bank’).

The creative possibilities in the push and pull of past, present and future times and hypothetical situations makes learning the more complex tenses a very valuable exercise for unlocking creative possibilities in your storytelling.

Mixing up irregular verb forms

Irregular verbs are those verbs that you don’t just plonk ‘-ed’ on the end of and call it a day. For example, the present, past simple, and past participle forms of these irregular verbs:

- Be (In present tense, I am, you or they are, he, she, it or other gender pronoun is). Becomes were/was in past tense (I was, they were) or been (past participle)

- Do (present), did (past), done (past participle, e.g., ‘she had done her homework’)

- See (present), saw (past), seen (past participle)

Using the correct irregular verb may avoid confusing situations such as confusions between verbs and nouns.

If you were to write ‘She seed the garden’, for example, the reader might think you meant to say a character sowed seeds, was doing a bit of gardening, rather than that she saw said garden.

Context coupled with verb misuse can easily combine to dial up the confusion.

Misusing conditional tenses

Conditional tenses express hypothetical situations, possibilities or conditions (as their name implies). For example:

- Zero conditionals: Express a condition that is true for now or always, e.g., ‘If ice warms, it melts’

- Type 1 conditionals: Express a present or future condition that is real. For example, ‘If you leave the ice out, it will melt’

- Type 2 conditionals: Show a time that is now or any time, and an unreal situation: ‘If you put the ice back in the freezer now, it will not be a puddle shortly’

- Type 3 conditionals: Give an unreal past condition and a probable outcome had that condition been met. For example, ‘If you had put the ice back in the freezer like I told you, it would not have melted’

- Mixed type: Refers to a time in the past, plus an ongoing situation now. For example, ‘If I had put the ice in the freezer myself, I would have ice now’

You can see how the latter types of conditionals lend themselves to admonishments, passive-aggression, in that they refer to unreal events such as dreaming about other outcomes had other choices been made. They create alternate timelines where we made it on time, caught that train. Therein lies a world of imagination and possibilities for storytelling.

Tips to avoid tense errors and mistakes

To keep a clear sense of sequence and condition:

- Learn and practice forming different tenses. Doing so shows there are so many ways to talk about the same sorry melted ice saga (per the examples above).

- Break sentences up into each relative, timed element. What happens when? Is the timeline clear?

- Learn regular and irregular verbs and their conjugations. Most people learn these in school, but we forget easily. Print out the ones you struggle with most and keep them at hand (or get Le Guin’s manual or another for handy reference guide).

- Unless there’s a good reason to change tenses, don’t. There are many ways to create an interesting sequence of events without time-travelling like it’s Back to the Future.

- Choose the appropriate tense. If you find you have to write a lot of ‘had had’ or similarly convoluted sentences (e.g., ‘He had had the party at McDonalds, ugh’), consider switching to a tense that uncomplicates the story’s flow (‘He had the party at McDonalds’).

- Get feedback. In a crit community, other writers will be happy to point out tense errors as they are the easier, low-hanging fruit to correct when you understand tense rules well.

POV and narration errors: Examples and tips

Point of view (POV) and narration are two areas it’s also easy to wrong, especially for beginners.

The core types of POV are (in order of commonality):

- Third person (narration that uses ‘he/she/they’ – third-person pronouns) – ‘It was inevitable: The scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love’ (Gabriel Garcia Marquez)

- First person (narration that uses the first-person singular (more common) or plural (less) – ‘I write this sitting in the kitchen sink’ (Dodie Smith)

- Second person (more uncommon, narration using the second-person pronoun ‘you’) – ‘You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. Relax. Concentrate.’ (Italo Calvino)

To this we add further types of POV, depending on involvement and breadth of knowledge, such as ‘limited’ (where viewpoint is limited to a character-narrator’s perspective) and ‘omniscient’ (an all-seeing, God-like viewpoint).

See more on POV in our complete guide to POV. On to common errors in viewpoint and narration.

Inconsistent POV (e.g. Head-hopping)

Point of view shouldn’t change between persons (e.g., I, he, you), or viewpoint characters, if there is zero signal or reason for the change. Otherwise, the reader is likely to be confused.

Head-hopping is when a writer switches between points of view in a scene, accidentally jumping into another character’s viewpoint without a clear transition or break.

One minute we’re reading Jack’s first-person POV, then suddenly we’re getting Jill’s thoughts, and we’ve forgotten the pail of water and the hill in the way POV see-saws.

For example: ‘I can’t believe we have to fetch the water. I’m annoyed and Jill doesn’t seem too fazed. Jill is thinking about running for president and isn’t bothered at all, wishing Jack wouldn’t be such a grumbling git.’

If we’re in Jack’s POV in first person, he wouldn’t know what Jill is thinking in this moment unless she’d told him. It’s possible we’ve ‘hopped’ to her viewpoint.

Head-hopping is confusing because it disrupts flow – we have to readjust to the fact we’re reading someone else’s point of view with no preparation for the change.

Impossible knowledge

The author may know everything that happens, but if a character has a fixed viewpoint, they cannot know what another character is thinking, has experienced, without some form of communication/revelation to them.

POV grows confusing when characters have knowledge of information they shouldn’t have due to not being God-like and omniscient.

POV is DISTANT AND TELLS MORE THAN SHOWS

If you use a lot of filter phrases (e.g. ‘Jack saw that… Jack felt that…’), the narrating voice becomes more removed from the character.

We see the character like a figure on a distant screen, then, the author’s puppet, rather than seeing through the involved narrator’s eyes (such as in limited third person). This is where the reader may see the author’s hand more, Oz the wizard twitching the curtain.

Compare:

‘Jack saw that the pail had a hole in it and felt that it was a futile waste of time.’ And: ‘The pail had a hole in it. How hadn’t he seen it before? Ugh, it was all a waste of time.’

The second, deeper POV gives a fuller sense of Jack’s in the moment emotions and reactions.

Deeper POV inflects narration with the character’s own outlook, vocabulary, voice. It draws on their unique persona to make even telling show character.

Tweet This

Inappropriate internal monologue

Switching into a character’s thoughts is useful at emotional moments in narration.

For example, you may have a third-person narrator and wish to show their reactions to events:

She arrived late to the games evening and everyone had already gone home. Oh gosh this is so embarrassing . . .

If every other line is in inner monologue, or a character’s in-the-moment thoughts interrupt scenes all the time, adjusting between first- and third-person pronouns POV constantly may become a little dizzying.

What’s more, too much interiority (the quality of being inside someone’s head) may make the story’s progress much slower.

It is often best to balance inner monologue with forward action (and other elements that lead focus outwards into the scene, such as description).

There may be exceptions, such as if you want a very interior, neurotic narratorial voice – a character who is all ‘head’.

Tips to avoid common POV and narration errors in writing

To avoid common POV and narration errors:

- Stick with consistent POVs and signal POV changes. If your story is narrated by four first-person narrators, try using each narrator’s name as a subheading preceding their chapter (or even replace chapter titles with their names – this will make viewpoint unambiguous).

- Watch out for filter phrases. A tell-tale word is ‘that’, e.g. ‘She understood that studying law would be a slog. She saw that there were scores of harried-looking second-year students in the law library.’ Reword the narration to show through the character’s eyes more, give their reactions.

- Balance internal thoughts with external events. Don’t let your narrator’s thoughts overwhelm everything else that is interesting and going on in your world. The author can at least notice the details their character doesn’t.

- Make a list of what each character knows, and what they can’t know. It may help you to keep tally on who knows what, and who doesn’t know what the reader knows about other characters’ thoughts, views, secrets, (mis)deeds.

What are other POV or narration issues that trip you up? Tell us in the comments.

Repetition and redundancy: Examples and tips

Repetition and redundancy are issues in writing that give prose a leaden, plodding effect. Repeating yourself or not varying the cadence of sentences may give readers déjà vu (that sense of ‘I’ve seen this before’), and not the thrilling, mystical-seeming kind.

Read on for common types of repetition and redundancy errors in writing, plus tips to avoid these issues.

Repetitive sentence structure

This is a common issue (especially if you’re using AI writing tools to produce whole chunks of your story for you – these tools’ outputs need editing). Beginning every sentence, for example, with a subject-verb-object structure gets tiresome quickly:

Jack wanted the job. His wife pushed him to apply. He checked his CV. Jack was nervous. He liked his comfort zone.

If we keep on with the subject (Jack or his wife), verb, object structure, the rhythm of the writing feels dead. Better to switch it up, find a change of rhythm:

Although Jack wanted the job, he was nervous. His wife had pushed him to apply but reading over his CV again, he realized the familiar was his handrail.

Not only does overreliance on the same grammatical structure feel wooden. Other ways of phrasing may emphasize cause and effect, push and pull, and the suspense of a situation clearer.

Tautology and pleonasm

Among common writing errors, tautology appears frequently. It means saying the same thing twice in different words. For example:

Jack wanted the job. He desired the position.

This is a basic example of tautology. Pleonasm is a type of redundancy where a word already encapsulates a meaning further words double. For example:

- ‘He returned the book back to the library’ (‘back’ isn’t needed as ‘returned’ implies a going back)

- ‘The wet water quenched his thirst’ (‘water’ contains the sense of fluidity or wetness)

- ‘She glared at him with her eyes’ (unless the subject has some kind of third-eye vision, what else would one use to glare at a person?)

Remember that you can always trust in the reader’s ability to infer, understand implication.

Name overuse (lack of pronoun substitution)

Another common type of repetition issue in style is using a character’s name every time narration refers to them. If it is clear who the subject is (for example, if your character is the only person in a scene), use pronoun substitution for flow. For example:

Jack wanted the job. Jack had scoured local listings and was one rubbish lead away from becoming a full-time clown with the It make-up to boot. Jack was tired.

This is too much ‘Jack’ – substituting with the pronoun ‘he’ where appropriate (and remembering to vary subject-verb-object structure) would improve flow.

Repeated words and punctuation

It is easy to accidentally press the speech mark key twice or enter a duplicate ‘and’. These common writing mistakes are easy to fix (read tips for avoiding repetition and redundancy in writing below).

Tips to avoid repetition and redundancy in writing

To avoid a ‘samey’ quality:

- Vary sentence structure. Try using more participles and other parts of speech that depart from ‘Sam I am’ subject-verb-object structure.

- Use find and replace. If you spot a doubled speech mark or word, use find and replace to search (for example ‘and and’) to fix any other instances

- Pay attention to inference. What can your reader already infer from the scene, individual words? Are you over-telling what’s what?

- Outline before writing. An outline helps you ensure each part has its place (if you wish to avoid repeating key story events)

- Paraphrase. Find other ways to express the same sentence. This is where an AI tool like ChatGPT can be helpful, as you can ask for (for example) ten variants of a clunky sentence and edit your favorite. Or as the tool paraphrased this last sentence, ‘Use ChatGPT to get ten sentence versions and pick [and edit] one.’

- Use transition words and phrases. For example, ‘because’, ‘meanwhile’, ‘on the other hand’. This breaks up monotonous flow.

Keep reading for tips on common tone and voice, argument, dialogue and description errors!

Tone and voice errors: Examples and tips

Tone and voice in writing are important for multiple reasons. Together, they supply:

- Character – a sense of who’s speaking

- Register – whether the writing is formal or informal, a technical or business document vs a fiction story

- Emotional context such as mood (for example, whether a situation is cheerful or bleak)

- Atmosphere: The overall quality of the mood of a piece of writing

Let’s explore common tone and voice errors in writing:

Inappropriate or inconsistent tone and voice

If tone and voice change in writing, it needs to be contextually clear why this change has occurred.

If Sherlock Holmes goes from the more formal register of ‘Elementary, my dear Watson’ to ‘Well the bleeding case is a doddle, innit?’ it’s jarring to read a change from a formal to slang register that doesn’t seem to fit the character.

Consistent tone and voice (that fit character, subtext and context) aid believability.

Absent or thin tone and voice

Tone and voice seeming either absent or weak is another common issue. For example, if an entire story is telling narration:

Sherlock Holmes examined the scene and clues were found. The case was solved.

There isn’t a sense of character or tone and voice in this telling narration. How does Holmes go about examining the scene? What does he find?

Tone and voice, like characterization, are found in the specifics.

Tweet This

Overusing technical language

Technical language such as jargon makes writing read more like a user manual than a story. For example:

Initiating pre-burn sequencing, the pilot commenced TLI protocols for optimal trajectory targeting. Utilizing the VMS, ascent rate and gimbal angles were continuously monitored to maintain thrust vectoring.

Unless the reader has specialist knowledge, they’ll be confused by niche words and phrases. All you need for the above is:

The pilot prepared for take-off.

Lack of personality

Jargon and thin tone and voice may make story feel devoid of personality. Look at memorable narrators from fiction, such as the angsty teen Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye. Salinger fills viewpoint narration with a character’s past, feelings, vocabulary. The reader feels Holden’s pessimistic outlook in the opening:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (Little, Brown and Company, 1951).

So how do you avoid tone and voice issues and fill your writing with personality?

Tips to avoid tone and voice errors in writing

To create effective tone and voice:

- Keep tone and voice consistent with context and subtext. If a character is struggling with a deep depression, for example, their word choice, attitude, emotion should reflect this in their speech or narration.

- Draw tone and voice details from character and context. For example, a writer who has had their manuscript rejected twelve times may write and speak more drily/wearily/comically/desperately about querying than a character sending out their first ever query. Think about how experience shows in (or inflects) tone and voice.

- Rewrite simpler. Jargon squeezing out personality? Think of the simplest possible expression of the core meaning, then color in attitude or outlook from there.

- Know your audience. If you’re writing for feel-good romance readers, they’ll be confused if you use flowery language like Nabokov. Consider genre and the soft limits on tone and voice it may impose (or not impose).

- Use clear and concise language. Avoid excessive jargon, or unnecessarily complex language that might confuse or alienate readers.

Next up: Common writing issues involving argument and logic.

Logic and argument flaws: Examples and tips

Common errors in logic and argument in writing create head-scratching moments, or even vehement disagreement in your reader. For example:

Hasty generalization

Watch out for generalizations that your reader will likely disagree with that could make your story frustrating. For example:

All kids hate school, and Tommy did not want the summer vacation to end.

The reader may say, ‘Hang on, my kid loves school’. Put specifics in place of generalizations.

Circular reasoning (or weak cause and effect)

Great stories come alive through cause and effect, one thing leading to another.

Circular reasoning cuts off a wider sense of cause and effect. For example, if you were to say:

The One Ring must be the most powerful artifact in Middle Earth because it was created by Sauron, who is the most powerful being; therefore, Sauron’s power proves that the One Ring is the most powerful artifact.

A more compelling way to suggest the ring’s superior power would be to show its own powerful properties in action (as Tolkien does).

For example, Tolkien shows how the One Ring corrupts and tempts even the protagonist’s friend and ally into trying to take it from him. Power isn’t the reason for its own existence, in this case, but is instead contextualized in dynamic, ever-shifting series of causes and effects, in power relationships involving action and reaction, desire and opposition.

Straw man arguments

A straw man argument misrepresents an opponent’s position to make it easier to attack.

For example, representing Muslims as scheming terrorists who uniformly hate ‘the West’ is an outmoded Hollywood action trope (and misrepresentation of the vast majority of Muslims who live peaceful lives) that some would say falsely justifies religious intolerance or military adventurism.

Misrepresenting others makes them easier to attack [a reader could easily say that this viewpoint is anti-war propaganda, for example, rather than admit that some stories uncritically support villainizing others]. ‘Lazy’ writing falls prey to straw men, easy targets.

False dilemmas or dichotomies

A false dilemma or dichotomy is when a scenario or situation is represented as having only two possible outcomes, when in reality there are or could be more.

For example, the saying ‘you’re either with me/us or against me/us’. Regarding the previous subject (straw man arguments), you can see how this ‘us vs them’ binary is limited/limiting (and seldom scratches deeper truths).

There are many other possible arguments and explanations. A person may disagree because they have a more nuanced take or because they see both sides. So often, there is a third way (or more).

To use another example, if you create a fantasy world where people either can do magic or can’t, what about people who could do magic once upon a time, but cannot any longer for some reason? Where does magic begin, end, and get interrupted (or corrupted)?

Thinking of these other possibilities outside of a binary or dichotomy helps to make stories more nuanced, and possibilities, arguments and positions more varied.

Tips to avoid logic and argument errors in stories

To avoid logic and argument errors in stories:

- Read through carefully for clarity. Does every reaction have an identifiable cause?

- Analyze argument. Is there any falsehood that your reader might argue with that context, character, or another story element cannot defend?

- Use robust evidence. Just as in an essay you’d need evidence to support claims, stories are somewhat evidence-based (we need at least anecdotal evidence of why the antagonist poses sufficient threat for a character to accept a call to adventure, for example).

- Be objective. How else could a reader interpret or read this scene or event? What might a reader with a different identity to your own object to or disagree with? Balanced research aids objectivity (for example, exploring viewpoints from both sides in a military conflict if creating a historical novel about a specific war). The more you understand, the better your argument will be.

What is a logic or argument issue in stories that frustrates you? Share in the comments.

Dialogue writing: Common errors in written speech

Common dialogue writing errors fall two broad categories:

- Content issues (e.g. unnatural dialogue, thin context or subtext, ‘as you know, Bob’ and on-the-nose dialogue)

- Formatting issues (such as differences between punctuating dialogue with speech attribution (dialogue tags) versus attributing using actions/gestures (action tags), starting new lines for changes of speaker)

Unnatural dialogue

Unnatural dialogue is speech that doesn’t capture how people actually speak. It lacks the realism and authenticity of true voices.

A classic example of this is ‘As you know, Bob’ dialogue. This is where the author shoehorns information into dialogue solely for the reader’s benefit, and the authorial intention of giving exposition is obvious. For example:

“As you know, Bob, this is a very important mission to the Gamma Galaxy.”

“Yeah, Tom, and you remember that Captain Starling doesn’t want any shenanigans.”

If two characters in conversation know all the information they’re discussing already, there’s no need for them to have the conversation, except for the reader’s benefit.

One way to solve this is to make dialogue allude to what characters know, but not tell everything. Another is to add further information previously unknown to either character. An example using both:

“So Captain Starling’s betting the farm on this mission, huh? Quite a mood he’s in this morning…”

“A mechanic back at port told me,” Cal lowers her voice as muffled footsteps grow louder in the corridor outside, “there’s this weird anomaly that’s been spotted in Gamma that’s been giving Cappy sleepless nights.’

Missing context/subtext

Sometimes dialogue is confusing when the context is thin or periodically disappears.

If characters start to feel like talking heads on green screen, it may be a sign the setting needs more coloring in between lines, in action tags or narrated description of how characters are feeling or what they’re seeing around them.

See how Kent Haruf gives the full context and subtext of a barber’s shop in Plainsong between lines of speech (and infers the subtext of two brothers being very private individuals):

I said, Who cuts your hair?

Kent Haruf, Plainsong (Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), pp. 40-41

Mother.

I thought your mother moved out. I heard she moved into that little house over on Chicago Street.

They didn’t answer. They were not surprised that he knew. But they didn’t want him talking about it in his barbershop on Main Street on Saturday morning.

Isn’t that what I heard? he said.

They looked at him and then quickly at the boy sitting against the wall. He was still watching. They kept watching and stared at the floor, at the clippings of men’s hair under the raised leather-backed chair.

[Ed’s note: Haruf does not include speech marks in the original text.]

Through context (the barber’s shop where there’s an unwanted eavesdropper) and subtext (private family situations the brothers don’t want everyone to talk about), Haruf creates a subtle sense of character and emotion in dialogue (the nosy barber, the recalcitrant brothers).

On-the-nOSE Dialogue

In on-the-nose dialogue, characters explicitly state thoughts, feelings or intentions, in a way that can read unnatural and unlike how people communicate on multiple levels – speech, body language, inference, allusion. Compare:

On-the-nose dialogue example:

“I’m angry at you because you lied,” John said.

“I lied because I’m an evasive person,” Susan said.

More natural dialogue with the same context/subtext:

“You let me down. Why didn’t you just say?” John stood in the doorway, arms folded.

Susan lay on the threadbare couch, pretended to be intently reading her book, but he’d been standing there a while as he tried to get himself under control. She hadn’t turned a single page. She must have heard him come in.

“Hmm? Sorry, did you say something?”

In the second example, each element contributes to a sense of conversation – body language, staging within the scene, details about what each character is doing (or has just been doing). This gives fuller context and uses inference better to suggest conflict of desires and confrontational vs evasive or avoidant behavior.

Misusing action and dialogue tags

Most of the common dialogue writing errors appear in using dialogue tags and action tags.

Dialogue tags:

- Attribute speech (and sometimes suggest the manner of speech, e.g., ‘She spat’ as a tag suggests fast, angry speech)

- Use a comma, not a period, at the end of speech (they continue the line) – “That’s right,” she said’

Action tags:

- Attribute speech (often using action/gesture to infer the tone and mood of the speaker)

- Use a period as they are a separate action/gesture to the spoken matter (“That’s right.” She nodded in case there were any doubt about her agreement’). You can’t ‘nod’ a spoken phrase, so it makes sense it is not written with a comma as a dialogue tag.

Tips to avoid common dialogue errors in writing

To catch common errors and make dialogue carry character and plot like Haruf’s example above:

- Lean on context/subtext. Where are the speakers (and why are they having this conversation? Why do any speakers say more, or less?)

- Assume smart readers. Don’t over-explain or give as an info dump what your reader can infer. If someone stamps a foot, slams a door, your reader will infer they’re angry

- Read dialogue aloud. This is excellent at catching unnatural dialogue.

- Make every character want something. This will ensure that underlying motives, desires, drive what your characters say.

- Use every available device. Action, description, mood, tone, setting – these all may come into your dialogue, avoiding ‘green screen’ effect.

For more on writing dialogue, see our complete guide to dialogue.

Descriptive writing: Common errors and tips

Lastly, descriptive writing is a vital part of immersive storytelling. Strong description involves multiple senses, such as smell, hearing and touch.

Common issues in descriptive writing include:

Imbalanced description

Too little description, and your reader sees the green screen coming through. Too much, and overwhelming detail clutters the page and detracts from pace.

Good description works together with other devices such as dialogue, action, pacing and tension, to strike a balance that draws the reader in and onward.

Tweet This

Unclear description

Specificity is an ally to clear description.

Instead of the haziness of ‘the girl seemed sad’ (and leaving it at that), the reader sees precise details that give this impression (such as the girl contributing less to conversation than usual if using subtler detail, or a stronger sign such as slumped posture, a downturned mouth, sad eyes).

Unclear or thin descriptive relevance

It is jarring when descriptive details seem superfluous to requirement. It may take the reader out of the story. For example:

She was nervous for the interview, and fidgeted on the cloth-upholstered, grey-striped fabric of the taxi’s back seat.

Would the reader care about what material the taxi’s upholstered in, in this example? What other descriptive detail may be more interesting (such as the music the taxi is playing, or what a character can see from the window)?

Overused or stock descriptions

There are many overused stock phrases and cliches that you can find other metaphors or similes to replace.

For example:

- ‘He had a heart of gold’ to express good-natured qualities

- ‘Her eyes were as blue as the ocean’

- ‘The lizard was as fast as lightning’

- ‘She was a beautiful goddess’

What else is a good heart like, could a lizard outrun, or does beauty resemble?

In Neil Young’s classic song ‘Heart of Gold’, he says he’s been a miner for a heart of gold, than that he’s crossed the ocean for one. The focus on the different ways the metaphorical heart can be found (digging down, traveling around) reinvigorates the overused term with a little more life, specificity (music is often also more allowing of clichés than narrative fiction, though, where they stand out without the sonic distraction or shifts between verse and chorus).

What that is more personal to your character (and less overused)?

Tips for avoiding common descriptive issues

To ensure description is impactful:

- Think about ‘need to know’. What does the reader need to know right now? What will give tone, mood, atmosphere concisely?

- Look for the specific sign/image. Poetry is useful to read for using concrete imagery in precise, concise, and creative ways. Replace sweeping abstract nouns (e.g. ‘melancholy’) with the specific details that suggest them.

- Draw from your world and characters. What vocabulary and concepts would be available to a visual artist versus a brick layer to describe? Or how might each surprise the reader in what they know, think, say that goes against assumptions for type? Play with conforming to and deviating from type.

- Show and tell. Sometimes telling is necessary (such as in a short transitional phrase between scenes, locations). Yet show as much as you can. Show signs someone is sad, instead of only stating so. Paint scenes with the senses.

- Be concise. Eliminate unnecessary descriptive words and phrases whose meaning context already supplies (see repetition and redundancy tips above).

Feedback on your writing will help you pinpoint the preceding ten common types of errors and learn from them, making steady improvement.

Meet a constructive, caring writing community and get extra perks such as weekly feedback, story outlining tools and webinars on story craft when you upgrade to The Process.

I rarely leave reviews, but in this case I make an exception. I had an evaluation done as I am a first time novelist. I received a insightful and impactful evaluation. I turn to the process of improving my novel and my writing with renewed confidence and greater insight. I highly recommend this service. – Herbert

12 replies on “52 common writing errors (examples and tips)”

Very useful tips. Thank you!

It’s a pleasure, Billy. Hope part two coming next week is useful, too. Thank you for sharing feedback.

I judge my progress as a writer not on the quantity of my errors, but on the variety. Number 10 (description and clarity) will always be my favorite 😉

Haha, same here, Margriet. My pet stumble is forgetting to close brackets (and ‘cemetery’ always gets me, I always spell it with an ‘a’ before the ‘r’ by mistake).

A most helpful post. Some of my pet hates are here.

I find I’m often guilty of a bit of head-hopping.

Thank you, Vivienne. Head-hopping is an easy mistake to make. What’s interesting is there’s a lot of confusion in the articles I was reading about it while preparing this article, such as the strange advice to never change viewpoint at all in a scene (I’m not sure what these advice givers would make of Virginia Woolf, or the dizzying POV changes in the spoof kung fu movie Shaolin Soccer). Provided the change is clear as well as who is narrating after the change, one can get quite experimental, as the Modernists did. Thanks for reading our blog and sharing your thoughts.

A most helpful post. thx

Hi Paul, I’m glad to hear that. Thank you for reading our blog and leaving feedback.

Really helpful – properly understanding the basic rules helps you decide when you want to break them or tweak them for effect.

Hi Barbara, thank you very much for leaving this feedback. Absolutely, the best experimental writing comes from a place of rule-understanding, I’d say.

Jordan, thanks for the detailed guide! I think it will become my handbook. Except this handbook will be on my browser 🙂

I’m just at the beginning of my path as an author. I’ve usually been busy just studying. And I turned to various YouTube channels like Studybay to understand how to write this or that essay. But as time went on, I realized that I didn’t want to be limited to writing assignments and other types of homework, so I decided to develop myself as an author too.

Hi Carly, it’s a pleasure! The beginning is the best part, so much to discover and experiment with. I think that’s awesome. Essay-writing is a useful skill to develop but fiction gives one a little more freedom to indulge imagination and play. I hope you enjoy the journey. Thank you for reading our blog and sharing your feedback.